-40%

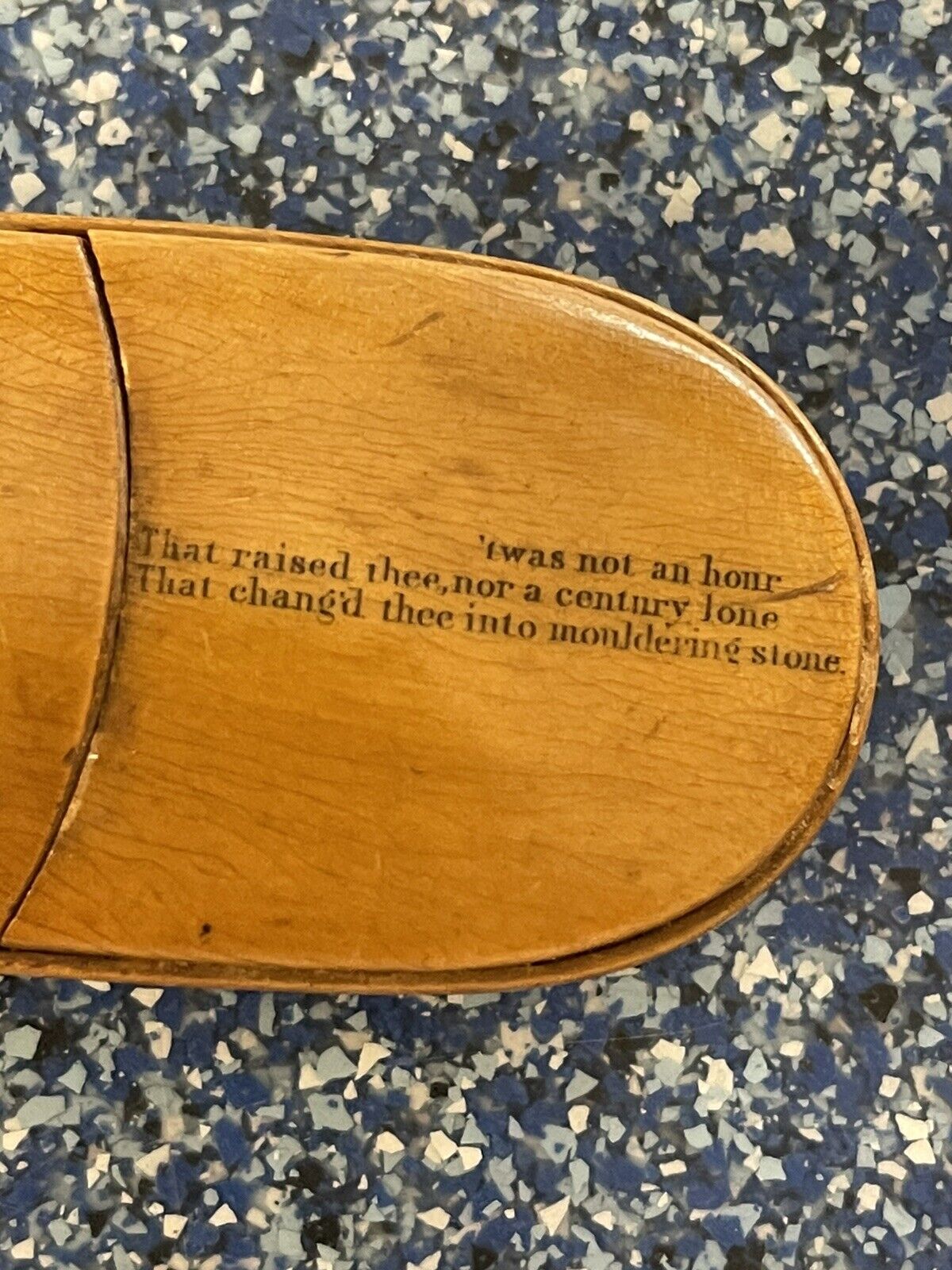

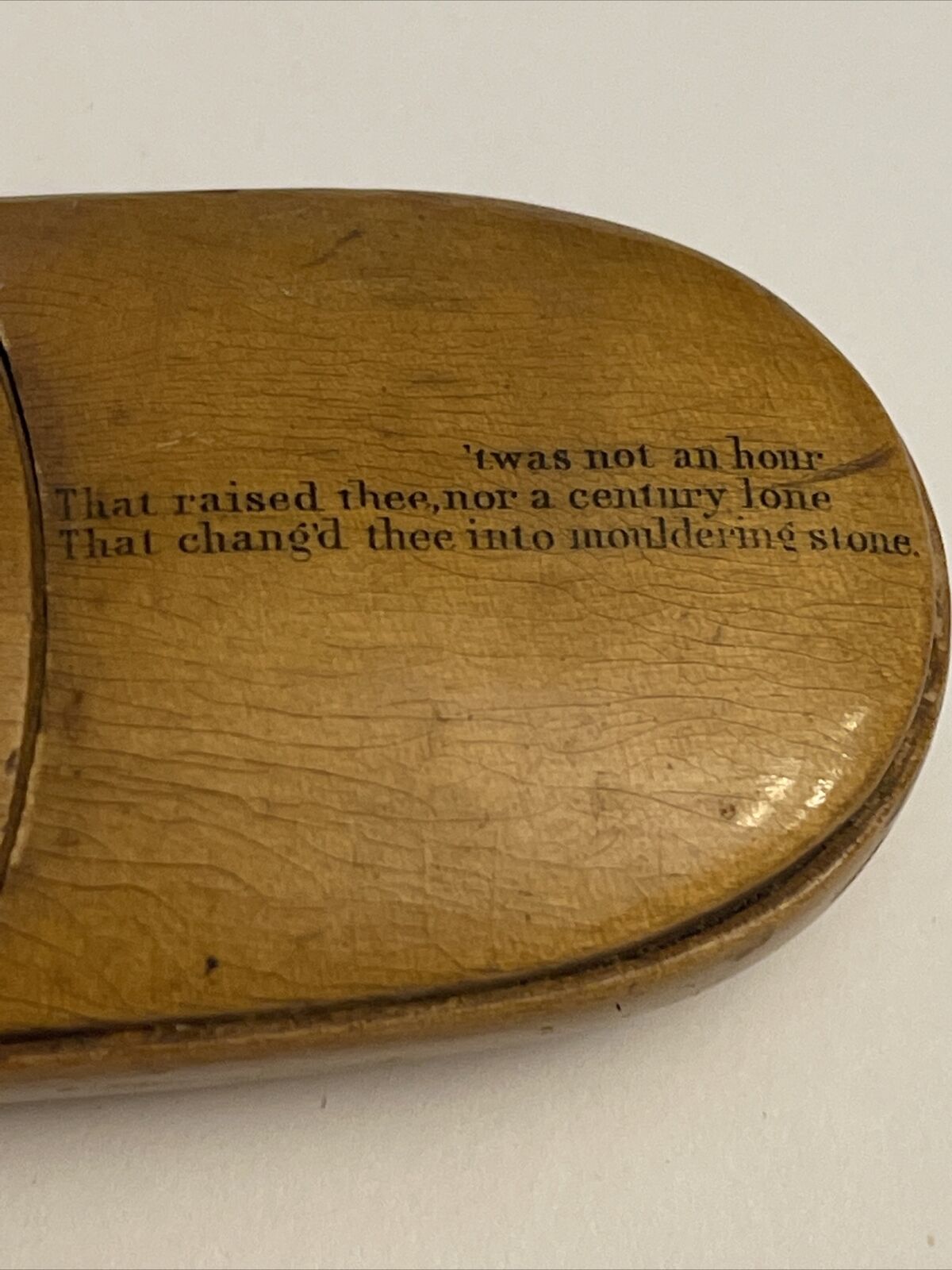

antique mauchline ware Glasses Case Rotehsey Castle as it was in 1784 Scotland

$ 52.65

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

antique mauchline ware Glasses Case Rotehsey Castle as it was in 1784 Scottland.

Mauchline(pronounced Moch’lin) Ware, a form of souvenir ware made by the Smith family of Mauchline, Ayrshire, now Strathclyde, Scotland, and favored by affluent Victorians traveling abroad.

Adorned with transfer ware scenes of landmarks, this Scottish wooden ware dates from about 1880 to 1900. Though it was sold throughout the United Kingdom, great quantities were also exported to many parts of North America, Europe, South Africa, Australia and elsewhere.

Mauchline, located 11 miles inland from the Scottish coastal resort of Ayr, was the center of the Mauchline Ware industry, which at its peak in the 1860s, employed over 400 people in the manufacture of small, but always beautifully made and invariably useful wooden souvenirs and gift ware. If it weren’t for the town’s association with Robert Burns, it would be difficult to find any present-day connection with the industry. Similar products were also made in Lanark, but because of the contribution its originators, W. & A. Smith of Mauchline, the vast number of souvenirs produced in southwest Scotland from the early 19th-century to the 1930s is now referred to by the generic name of "Mauchline Ware."

Mauchline Ware developed partly by accident and partly through necessity. Towards the end of the 18th century in the town of Alyth, Perthshire(now Tayside), a man named John Sandy invented the "hidden hinge" snuff box. He made the knuckles of the snuff box’s hinge form alternately from those of the lid and the back of the box, with a metal rod passing very precisely through the enter. This rod was a little shorter than the box so as not to protrude through the ends, which he then plugged, rendering the mechanism invisible.

Since Sandy was bedridden for most of his life, Charles Stiven, from Laurencekirk, took over the job of manufacturing and marketing this invention, thus it became known as the Laurencekirk snuff box. Eventually, the secret of the hidden hinge found its way to Cumnock, only a few miles from Mauchline.

William Crawford began manufacturing the hidden hinge snuffbox in Cumnock around 1810. It’s believed that he copied the hidden hinge mechanism from a box brought to him for repair. Unable to keep the secret to himself, it spread to at least 50 other Scottish snuff box manufacturers in the early 1820s, most of them in Ayrshire. These included William and Andrew Smith of Mauchline, whose family had formerly made razor hones.

Craftsmen hand decorated early snuff boxes using either colored paints or pen and ink. Then they gave the finished boxes numerous coats of varnish, which enriched the final appearance as well a protected the surface. Highly skilled artists created coaching scenes, field sports and "drinking" topics, all favorite topics for snuff box decoration.

With so many manufacturers, snuff box production continued at an all-time high, but the habit of taking snuff was on its way out. Although they made mostly snuff boxes, manufacturers like W.& A. Smith also produced other items, from postage stamp boxes to tea trays, all out of wood. The first of the new products were tea caddies utilizing the hidden hinge. In fact, they were so highly prized that when a female employee got married she was given a Smith's Box Works tea caddy as a present.

Over the next century, the Smiths of Mauchline and their competitors produced tens of thousands of articles in hundreds of styles and in several different finishes. They generally used sycamore wood, which has a very close grain and a pleasing color. The precise date of the first transfer wares isn’t known, but they companies manufactured them from the early 1850s until 1933.

Woodworkers created more items with transfer decoration than any other finish. These were true souvenir wares, since they decorated each piece with a view associated with the place of purchase.

Skilled craftsman applied transfers to the finished articles prior to coating them with several layers of slow drying copal varnish. This process took from 6 to 12 weeks to complete, although it seems that they must of developed an accelerated means of varnishing to cope with the sheer scale of production. However, this lengthy and careful process of manufacture accounted for the extreme durability of these products, many of which have survived in near mint condition.

As with earlier hand-decorated snuff boxes, manufacturers used sycamore wood, known as "plane" in Scotland, its pale color making an excellent background for the black transfers. While the majority of Mauchline Ware items were small, thus warranting only a single transfer, it was by no means unusual for craftsmen to apply six or more transfers to some of the larger pieces. Where they applied more than one transfer, the views were always related to one another, either by subject or geography.

Views of Scotland dominated the transfer ware. "Burnsian" views, by far, formed the largest single grouping and views associated with Sir Walter Scott probably the second. In addition to virtually every town and village, producers immortalized a great number of beauty spots, country houses, churches, schools, ruins and even cottage hospitals in transfer ware. Other views included seaside resorts and the inland spa towns of Malvern, Cheltenham, Chester, Bath and Harrogate, which became increasingly accessible to a growing number of people as a result of the rapidly expanding rail network. The Isle of Wight was particularly popular, probably due to Victoria's love of the place. And the popular south and east coast resorts--Brighton, Eastbourne, Hastings, Margate and Scarborough--saw their share.

Makers didn’t forget the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey, as well as Stratford-upon -Avon, a close rival to London. They even used some less obvious places, possibly because of an anticipated tourist boom which failed to materialize.

It seems that, contrary to popular opinion, manufacturers didn’t update views to reflect changes of fashion, transport and indeed of the towns, themselves. They introduced new transfer scenes as more and more places were considered sufficiently commercial, but revised few, if any, of the early views.

And although motorized transport became increasingly common from the mid-1890s on, few scenes show any form of motorized transport, but rather show the places, themselves. Indeed, railroads, as old as transfer ware itself, have very little representation, with locomotives appearing in only a handful of views. This suggests that companies made most of their transfer plates before 1880, producing few after 1890.

Although Mauchline Ware production continued for another 40 years or so, its popularity began to decline, so the cost of producing a large number of new plates would possibly have been prohibitive.

With the advent of photography in the latter part of the 19th century, many Mauchline Ware manufacturers turned to using photographic images as an alternative to transfer printed views. Today, collectors refer to these pieces as stick-on photographic ware. Although manufacturers probably introduced photographic ware 20 to 30 years after the first transfer-decorated items, collectors have found examples throughout the range of production of Mauchline Ware. Tea caddies, snuff boxes, and cigar boxes, which virtually ceased production by the time the first photographic image was used in the mid-1860s, are obvious exceptions.

It's quite possible that the first use of photographic images coincided with the establishment of the Caledonian Box Works in Lanark in 1866, since Archibald Brown, its founder, had a keen interest in photography. and made his own cameras. As a former employee of W.&A. Smith, he couldn't compete successfully with them making the same wares. Also, he was a friend of George Washington Wilson, perhaps Scotland's best known photographer, and used his work extensively on his products.

Producers of Mauchline Ware employed photographic views taken, in most cases, between the 1860s and the turn of the century. All were of good quality, and from a historical point of view, are of far greater interest than transfer views in that they’re factual. W.& A. Smith also produced photographic ware, but due to the overwhelming number of their transfer ware items, they undoubtedly preferred the more delicate transfer ware.

From the 1830s on, makers produced a steadily decreasing number of snuff boxes while producing an increasing array of needlework, stationery, domestic and cosmetic items as well as articles for personal decoration and amusement. In addition, companies created an incredible range of boxes in every conceivable size and shape and for limitless purposes.

Tea caddies and cigar boxes were the first of the new lines, but by the middle of the 19th century, when the industry was at its peak, virtually anything which could be made from wood and was comparatively small and served a useful purpose, found its way into W.&A. Smith’s and others’ product lines.

Needlework items—containers designed to hold or dispense cottons, threads, silks, ribbons, wool, string, pins and needles—were the most popular and made in assorted shapes and sizes. In addition, makers offered darning blocks and mushrooms, scissors cases, containers for knitting pins, crochet hooks and bodkins and a remarkable range of novelty thimble containers and tape measures. Among the most attractive sewing items were the egg-shaped sewing "etuis," varying in size from bantam to duck eggs. When opened, each revealed a hollow dowel with a removable top fixed to the base of the egg and designed to hold needles. A small cotton or thread spool was passed over the dowel and a thimble completed these portable sewing companions.

A great many cotton, thread and ribbon manufacturers—J & P Coates, Chadwicks, Clarks Glenfield, Kerr and Medlock—purchased Mauchline Ware containers for their products, their names clearly yet discreetly displayed either inside the lid or on the base. Thus, manufacturers transformed rather mundane accessories into attractive gifts.

Stationery items ranged in size from large blotting folders down to small bookmarks, including cylindrical rulers, some incorporating a pencil and rubber eraser, while others were covered in a mass of postal information. Rulers containing erasers and pencils became instantly recognizable by a small knob at one end for the pencil and a much larger one for the eraser at the other. Producers also turned out novelty inkwells, pens, pencils, pencil boxes and letter openers, as well as many designs of bookmarks including a patented combined bookmark and paper cutter.

Mackenzie and Meakle also produced boxes for postage stamps of one, two, or three denominations, and offered circular single denomination boxes. And they fitted the larger boxes with slopes to facilitate easy stamp removal. Often they used a portrait of Sir Rowland Hill, the founder of England’s Penny Post, to decorate them.

Although wood isn't perhaps the most obvious material for making jewelry, the more creative producers of Mauchline Ware made a number of attractive earrings, brooches, and bracelets, the more expensive of which, made around 1860, featured hand-painted segments.

Victorian ladies held their parasols with delicate Mauchline Ware handles, and since gloves were an essential part of Victorian dress, manufacturers like W.&A. Smith, also made glove stretchers.

Accessories for the Victorian lady’s dressing table included ring trees and powder puff boxes as well as clothes and hair brushes. One of the most unusual items was a flower holder. Containers for cosmetics included boxes designed for face powder, rouge, cold cream and lip cream.

The makers of Mauchline Ware didn’t forget the home, either, napkin rings being the most common item. They produced an assortment in all sorts of finishes until the 1930s. Often they numbered the rings from one to six, forming part of a boxed set. Occasionally, a collector will come across a ring set numbered up to 12. The Victorian breakfast table may well have been graced by a Mauchline Ware egg cruet, individual egg cups, and several versions of egg timers, both free-standing and wall mounting. Manufacturers produced candlesticks and vases, as well, in a variety of finishes, as well as the more costly (and rare) versions produced from two contrasting woods.

Since matches were essential to the Victorian home, makers assembled a wide assortment of match containers. Some were no more than novelty matchboxes serving no additional purpose, while others incorporated a bone holder for an individual match. Often erroneously called "go to beds," this type could serve as a candle providing light just long enough to get into bed. Their true purpose, however, was to melt sealing wax without burning the fingers.

Containers for money ranged from small ladies' purses to a wide variety of money boxes. While producers often made them in the form of chests and castles, the most unusual shape was that of a locomotive. They also made trick money boxes, which can generally be found either in almost mint condition, indicating that the child had despaired of extracting his or her money and had given up trying, or in very poor condition, showing that youthful patience had been exhausted and various implements had been used as safe cracking tools.

Collectors have found at least three district versions of eye glass cases. And with the popularity of photography, manufacturers produced Mauchline Ware picture frames of all styles and sizes, as well as photograph albums with wooden covers.

The Victorians loved to play card games and Mauchline Ware manufacturers satisfied this craving with boxes for one, two or even more packs of playing cards. Usually these boxes had three miniature cards glued to the top to indicate their purpose. But they also made cribbage boards, bezique markers, dice shakers and Chinese puzzles to satisfy the hunger of Victorian entertainment.

And manufacturers didn’t forget the children. Skipping rope handles, tops, popguns and whistles all found in their way into Mauchline Ware.